By Steve Smith

This quick blog really acts as a bit of a request. When researching the earliest days of Toc H, it is clear that no gathering of the Movement can end without all present singing the marching song, Rogerum. I set out on a quest to find a recording of this song in the style of a group of men singing. This has proved a Sisyphean task, yet to be fulfilled.

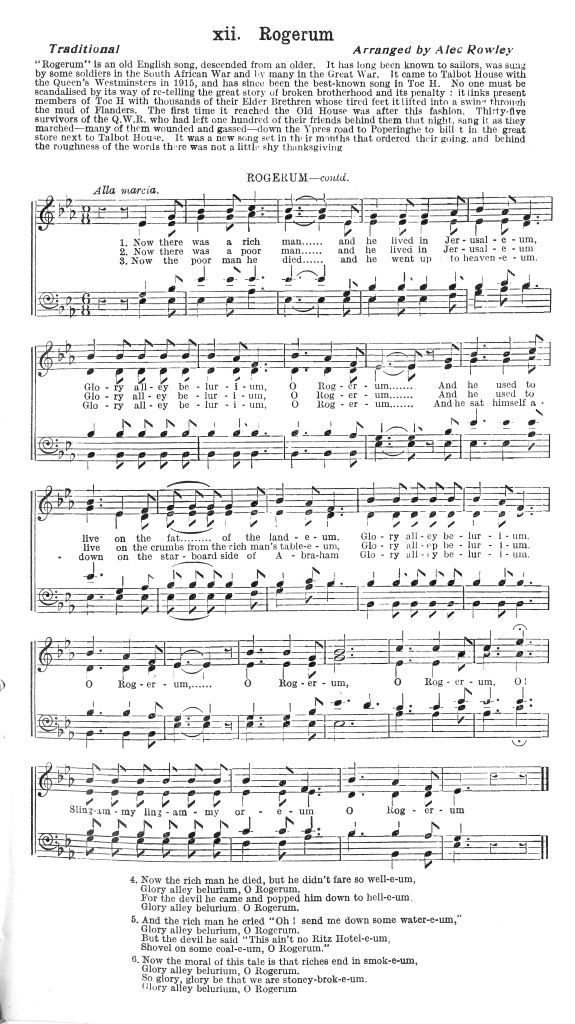

Let me explain how this song came to Toc H, and a little of its history. According to the Toc H Songbook (1930), where it was published in an arrangement by Eric Rowley, it was an old English song known to sailors, and was sung by some soldiers in the South African war and many in the Great War.

It arrived at Talbot House with the Queen’s Westminster Rifles in 1915. On the night of the 23rd of December 1915, thirty-five survivors of the regiment sang it as they marched from Ypres to Poperinghe, where they were billeted in the big storehouse next to Talbot House. Behind them, they left a hundred dead comrades – killed in a gas attack on the 19th and 20th – and the song was said to be a link between the living and the dead. When Toc H adopted it post-war, it was to link the members with the Elder Brethren left behind in the mud of Flanders. Its popularity was enhanced, when Dick Horne – of the QWR – made it famous at the Fancies, a concert party for the Sixth division. Tubby always said that it’s onomatopoeic chorus “lifted the feet of thousands of men [..] out of the mud and clay”. He even said that it helped hold the Salient.

Another example of the song’s place on the Salient is taken from The Old House – A Handbook for Pilgrims, published as a Supplement to the Toc H Journal December 1930

Let us gain another glimpse from the pen of a soldier* who was temporarily attached to the domestic Staff at that time:

“The Old House has shut for the night, the last Straggler has been ejected, the last penny has been taken at the canteen for a hurried cup of tea, but as yet no move has been made to turn out the lights on the ground floor. Visitors are expected. By special permission two Companies of Infantry billeted nearby are coming in for a late concert. In the hop-loft across the garden the Sunday furnishings have been carefully stored away and the Stage has been set with old sheets of canvas to form wings and back cloth.

The tramp of marching men is heard and the stirring marching song O Rogerum reverberates through silent Pop; our guests have arrived. Crowding in with cheery badinage to all and sundry they file through the House and take their seats in the hop-loft as keenly interested as if they were in the pit of their own local theatre at home. The concert begins, but not before a dark and secret conference between Tubby and the musical director has taken place to decide how some half a dozen scratch turns collected in the course of the day by the former are to be sandwiched into an already complete programme. Now all is arranged and Tubby steps on to the platform to open the proceedings with a cheery word to the troops.

(The concert is then described)

The concert is over, the Commanding Officer has made a speech of thanks, the troops have given three cheers for the artists and away they march to their billets with Rogerum helping them along. The Staff lock up and retire to rest hoping the concert will, however slightly, have helped their comrades to face Still cheerfully’ the horrors and rigours of the Ypres Salient.

*Robert H Brewster of the QWR, attached to the house following the Somme

So, what do we know of the song’s roots? Described by Tubby as a Minstrel song – though using a no longer acceptable term – it is said to be based on the 15th century Dives and Lazarus, Luke 16: 19-31. It was seen in print at least as early as 1558

As a folk song, it is recorded as Child 56. The Child Ballads are 305 traditional ballads from England and Scotland, and their American variants, anthologized by Francis James Child during the second half of the 19th century. The catalogue describes it thus:

The rich man Dives or Diverus makes a feast. The poor man Lazarus comes to Dives’ door and repeatedly begs ‘brother Dives’ to give him something to eat and drink. Dives answers that he is not the brother of Lazarus, denies Lazarus food and drink, and sends his servants to whip him and his dogs to bite him. However, the servants are unable to whip Lazarus, and the dogs lick his sores instead of biting him. As both men die angels fetch Lazarus to heaven, and serpents take Dives to hell. In version A, Dives asks Lazarus for a drop of water, and complains about his eternal punishment.

Toc H adopted it wholeheartedly when the Movement was reborn after the war. As well as being sung at meetings and festivals, it was belted out whenever a group of Toc H men came together. It is reported as being sung in places as diverse as Cardiff railway station and the Guildhall (where the Band of the Grenadier Guards desperately fought to keep pace of Tubby’s changes of pitch and tempo). During the 1922 trip to Oberammergau, Tubby recounts that, the party having just arrived in Germany at Aix-la-Chappelle (Aachen), began to sing on the station platform.

The red-hatted and red-faced German stationmaster bore up through the first hymn from the Beggar’s Opera, but Rogerum was too much for him. He asked us to be silent, but we sang; he commanded us, but we smiled as we sang. He turned from German to French, and back again. Troops on parade remained in a state of delighted mutiny. It was most discreditable and most harmless. Finally he rounded on the interpreter of the party. ‘I will have order! What sort of people are these of yours?’ The answer provides the summary of the party. ‘All quite mad, and yet all quite nice people.’

Of this song, Tubby says “No one must be scandalised by its wording, which at least helps to make the social moral of the parable more forcible than ever. That moral surely is that lovelessness is the ruin of the world. Whatever barriers we build to shelter us, or ditches we dig to separate us from the less fortunate in this life become walls and gulfs against us, when we would ask from them a share of the good riches of the life beyond”

The song was not without controversy, and in the February 1927 Journal, it was felt necessary to explain the song to the readers. Forgive me for reproducing the entire article, but I could not write it better myself.

Historically Rogerum is the song both of Talbot House in Flanders and of Toc H everywhere from the first. It has offended some who have heard it, without explanation, for the first time: it continues to offend a few, who have heard it often and whose feelings must be respected; while here and there a Branch or Group has sung it at every meeting— not freely but as a piece of conscientious routine – until it has become merely dull. Whether sung often or seldom, it is deeply cradled in the story of Toc H, but it is not, of course, our exclusive property. Other bodies—sailors, soldiers and some troops of Scouts— have long used it, and a writer in a London newspaper lamented that it was not chosen, among other ‘sea-shanties’, by the League of Arts choir at an open-air sing-song in Hyde Park last year (June 11), while a recent writer of sea stories (R. F. Rees, Harvest of Storm, 1926) puts a somewhat debased version in the mouths of his sailor-men. Tubby now relates again, as he has often done, the gallant conditions of its origin in Toc H, and makes some suggestions as to its proper use by our members —ED.

Rogerum is far from being a modern blasphemy, as some evidently imagine. It is directly descended from a much cruder Christmas Carol of the fifteenth century, well-loved throughout England in the age of faith. These songs, like the Miracle Plays, were intentionally crude, in order to get through to the minds of simple men, and carry—with a touch of fun—a simple democratic lesson; they were rough instruments which the Church was too wise to disdain and profited by for centuries.

Secondly, it is more than likely from the point of view of scholars that there was a touch of humour in the story of Dives and Lazarus as Our Lord first told it. The picture of the two men with their positions radically reversed is drawn in an arresting way, and Aramaic students are agreed that in the Parables crude colours were deliberately used with the same intention.

Thirdly, many lessons can be drawn from the story. The sting of it probably lies in the final reply of Abraham to Dives that a mere miracle cannot convert. Nearly all the sermons that have been preached on it ignore this point altogether, and take it in some sense which is merely secondary and remote from Our Lord’s original intention. It is clear that the main social meaning of the parable is that a rich man who shuts himself up behind high walls and leaves his brother to starve outside them, is likely to find that every barrier he builds with his riches between himself and his fellow men becomes in the next life a barrier which hedges him out of heaven, to which the patient poor pass joyfully. It is surely no ill service to the cause of Christ in society to say this in the form of a coon song; for it was in the plantations that our present version of Rogerum originated, and I can scarcely believe that anyone would condemn the plantation songs en bloc—crude though many of them are—for they come from the hearts of a people who love Christ in sincerity.

Fourthly, for the survivors of the Salient, and especially for such as Bert Stagg (of Madras) and myself, Rogerum has a warm place in our hearts; for the moment its glorious lilt breaks out (quite apart from the words) we can see the indomitable figures of our friends, moving with marvellous cheerfulness under conditions of most unutterable suffering and danger. The first time, I think, 1 heard it sung, was by thirty-five survivors of the Queen’s Westminster Rifles who had left one hundred of their friends behind them that night, and swung down into Poperinghe, many of them wounded and gassed, to billet ii the great Store next to Talbot House. It was a new song set in their mouth that ordered their going, and behind the roughness of the words there was mor than a little shy thanksgiving.

Men must have something to sing, and—apart from Cromwell’s Ironsides—few Christians have sung psalms and hymns upon the march; if you read the records of the Covenanters you will find how terribly the practice of singing, psalms and hymns encouraged hypocrisy and blasphemy of a far deeper kind The alternative, therefore, was not between Rogerum and songs of holiness but between Rogerum and really infamous parodies of popular hymns, ant songs beyond these terribly debased. So under the circumstances we welcomed Rogerum, and we welcome it still.

It is; however, to be used with every safeguard as the privilege of member only. I am strongly opposed to it being sung publicly to audiences who know nothing of its origin, or its sacred associations with the dead of Flanders On no account should it be sung, or taught, by Toc H to Scout Troops, Boys Clubs, etc. I have always set my face against this, and have, I hope, succeeded it stopping it almost everywhere. Moreover, I think that I can conscientiously say that I have never sung it myself without an explanation beforehand of the reason why. I do not deny that it is dangerous, like all strong meat; but it is strong meat for men, and if properly explained and understood will continue lead them on. Surely we must revolt from the conception that Our Lord prefers the musical modulations of a Minor Canon to the clean free Marching Song of men who were learning to laugh at fear, and to move together to their duty.

Frustratingly, a Toc H version from a Birmingham party was broadcast by the BBC at in 1923 but nothing was recorded prior to the BBC getting their first recording machine 1932, and it was only broadcast live.

Barney Baley, a well-known human rights activist, says Hi-Jo-Jerum was a marching song when he was with the International Brigade during the war in Spain, 1936-39.

It was still sung by Toc H – particularly when Tubby was present – into the 1950s but much less frequently. In 1958 it was said that a tape of the London Toc H Male Voice Choir was to be made of this and other songs. I have been completely unable to track down a copy of this tape. Even the archive in Birmingham doesn’t appear to have a copy.

In the sixties, Rogerum barely gets a mention, and after Tubby’s passing, is not spoken of in print, at all.

And after all this waffle, how about you have a listen to the song.

Here is a version sung by Dermot Leahy at Hugh Shields’s house, Dublin. Recorded by Hugh Shields on July 4, 1968

Here is a more contemporary version by the Mary Wallopers under the title Rich Man and the Poor Man

This link gives a simple excerpt of the song

https://www.hounslowwoodcraft.org.uk/assets/audio/hi-roger-rum

So, to close, let me reiterate that I have not been able to find a version sung by a choir or a chorus of men, as Toc H would have sung it

If anyone can point me in the direction of such a version, I would be most grateful.

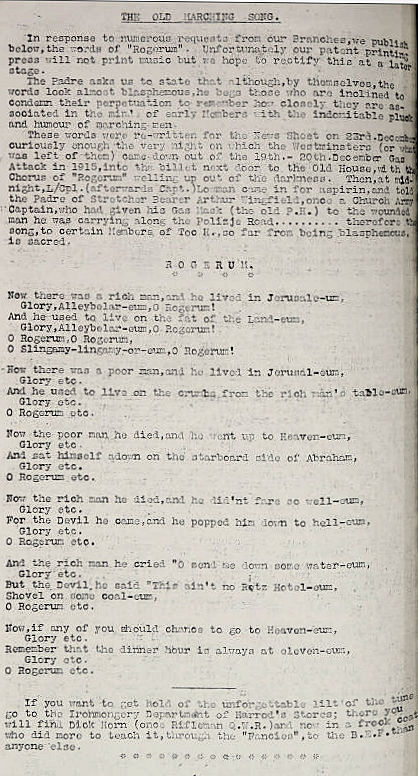

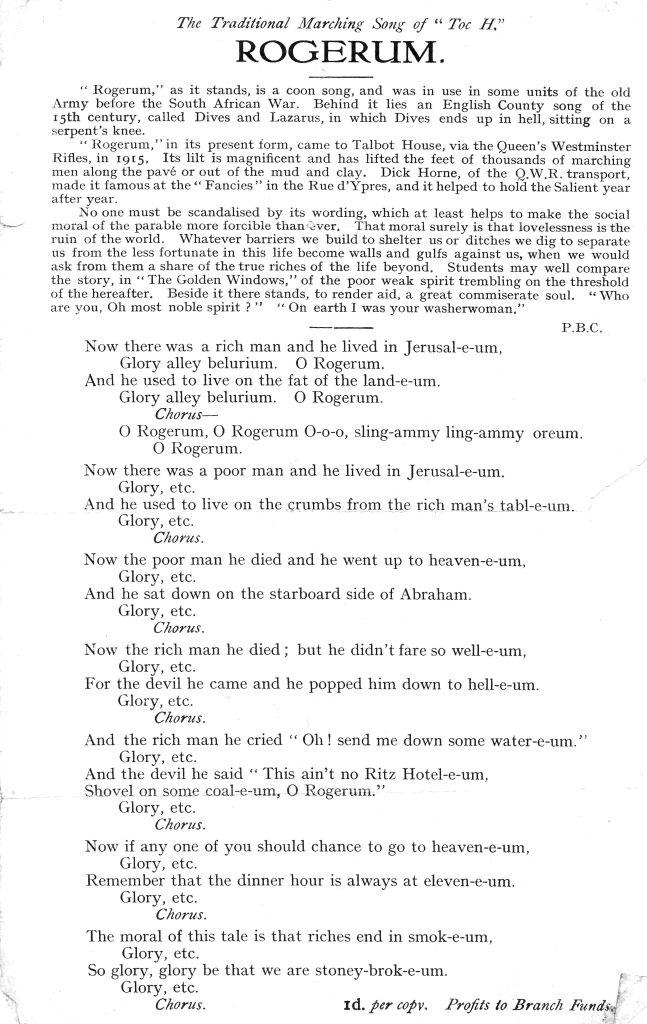

Images: Three versions of the words published by Toc H.

- As printed in the Toc H News Sheet (January 1922)

- As a song sheet (Date unknown)

- In a songbook (1930)

Notice the slight differences in words, especially the ’nonsense’ refrains after each line.

Alternate Titles

Rogerum

O Rogerum

Oh Rodger Rum

Old Rodger Rum

Rye-Roger-Um

Hi Roger Rum

Hi Ho Jerum

Hi Rosherum

Roy Roger Um

Dives and Lazarus

Diverus and Lazarus

The Walls of Jerusalem

The Rich Man and The Poor Man

Wonderful! Keep going, Steve!! Chris S

LikeLike

Thanks Chris

LikeLike