By Steve Smith

To say Charles Wakefield made his money in ‘black gold’ and spent it on fast cars and fast planes is true but misleading. He was essentially a successful motor-oil merchant, not quite an oil baron, and the fast cars and planes were not him living a hedonistic lifestyle but rather serving a desire to support others in their pursuit of speed and adventure. He was even known as the Patron Saint of Aviation, championing not just the pioneering solo fliers but also the rapid growth of commercial flights during the early decades of the 20th century.

And this was by no means the only outlet for his acquired wealth. He was a philanthropist of some note who supported many a worthy cause including the one that explains why I am even writing about him. This of course was Toc H, and although Lord Wakefield did not dedicate as much of his life to the organisation as some whom I write about in this blog, what he did do for the Movement resonates to this day.

Wakefield (Left) at a Toc H Birthday Festival

Beginnings

Although born in Liverpool, he came to love London especially the City which was a passion he shared with Tubby. And he loved people, particularly the disenfranchised and disadvantaged. And most of all he loved children.

“Never let us forget the Tiny Tims of humanity” was one of his favourite expressions.

Charles Cheers Wakefield was born in Kirkdale, Liverpool, the youngest of six children of John Wakefield, a clerk at Custom House, and his wife Margaret. The family were Wesleyan Methodists and John was a lay preacher. John’s brother Thomas was a missionary for the United Methodist Free Church and lived in Kenya for 25 years. The family – including our Wakefield when he grew up – would be greatly influenced by Charles Garrett, the pioneer of Wesleyanism in late 19th century Britain. Garrett’s Liverpool mission was up and running ten years before those in London and Manchester!

Wakefield’s birth date – 12th December 1859 – would take a new significance when he later became involved with Toc H since he shared it with Tubby. It was also the date – in 1915 – that Holy Communion was first taken in Talbot House on the day after the doors opened.

Wakefield’s baptism took place at the newly built Grove Street Wesleyan Chapel on the 23rd February 1860. Cheers was not an affectation added later in life as was sometimes believed but his mother’s maiden name with which he was baptised.

Painting by Oswald Hornby Joseph Birley http://www.artuk.org

Childhood

By the time he was 11, the family were living in Wavertree, then still fairly-much a village on the outskirts of Liverpool but soon to be engulfed by the city. He attended the Liverpool Institute, a Grammar school known as the Liverpool Institute and School of Arts in Wakefield’s day, famous for pupils such as Paul McCartney and George Harrison almost a century later. Wakefield was there in an era when Anthony Trollope regularly doled out the prizes although I found no records of our man being awarded anything significant. Nevertheless, he was well-read and enjoyed nothing less than William Shakespeare, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and John Ruskin.

He was described as being “of sturdy build, heavy in the shoulders, short in the neck, and yet slim-waisted and of exceeding quickness of the feet” and so, perhaps unsurprisingly, was a keen sportsman. He enjoyed football, cricket, running, and by all accounts he was a highly competent boxer though his soubriquet was the Smiling Boxer because he never lost his temper and always kept a smile in his eyes.

It was on the football field that he met one of Charles Garrett’s sons and this would lead to his religious transformation. He moved from the dogma of heaven and hell to the sense that being a good Christian meant doing good deeds. He joined the Young Men’s Christian Association around 1875 when in his teens.

As he grew up and entered his twenties he competed in athletics competitions at Wavertree Cricket and Football Club. He also played rugby for the club and was Honorary Secretary for a time.

Beyond sport he was developing his philanthropic interests and was a voluntary worker with the Free Churches teaching Sunday School at St Paul’s Wesleyan Church, Old Swan for many years.

A Career Begins

Career-wise, by the time he was 21, he was employed as a book-keeper for W & F Walker, oil merchants, at Irwell Chambers, Union Street. William, Frank (and Richard) Walker established their business in the late 1860s and dealt in oils and paints. Colonel William Walker, the senior partner, was well-regarded both as a business man but also for his public service. He was a Justice of the Peace amongst many other things, and both he and Frank were officers in the 18th Liverpool Rifle Volunteers (Liverpool Irish), a Territorial regiment. This sense of civic duty may well have influenced young Charles Wakefield.

Wakefield was clearly ambitious and in 1885 – when he was 26 – Vacuum Oil, an American company producing lubricating oil, opened a sales office in Liverpool. Wakefield was, in modern parlance, head-hunted, as the American giant had heard about a young man in Liverpool who was knowledgeable of all matters pertaining to oils and lubricants. And so he left Walkers for the Vacuum Oil Company.

Their sales office was on the first floor of the Albany Building on Oldhall Street. Built in 1856 for Richard Naylor and designed by James Kellaway Colling, it was meant as a meeting place for cotton brokers (and clearly other businesses) with offices and meeting rooms, together with warehouses in the basement. From here, Wakefield plied his oils. He also became a freemason in 1886 when he joined Royal Victoria Lodge, doubtless interested in both the philanthropy of Masonry as well as the benefits to his business.

On the 17th February 1887 Wakefield married Sarah Frances Graham at Victoria Park Chapel, the new Wesleyan Church which actually stood in Olive Vale. The Grahams did not appear to be Non-Conformists though the marriage was carried out under a Methodist liturgy by Minister Josiah Slugg. Absent was Sarah’s father William, who had died in 1870 when Sarah was just 11. Sarah was listed as an Insurance Writer at the 1881 census. They would live on Russian Drive in the West Derby area of Liverpool and then briefly in a Beech Lea opposite the Botanic Gardens.

Lady Wakefield and Freda by Charles Haigh Wood

And as Wakefield set out on the path of marriage, his business life was gathering pace. In February 1888 he was elected to the Manchester Chamber of Commerce. That same year we see one of his first registered patents when, along with Walter Grimes, he registers a patent for a sight feed lubricator. Over his lifetime, Wakefield and his companies filed dozens of patents for lubricators, oils or other related inventions and improvements to the same. Perhaps most notable was the Wakefield Lubricator that bore his name.

He was also well travelled as he sought new sales leads abroad. In September 1890 he travelled to Bombay to open an Indian office for Vacuum Oil.

In September of 1892, a fire broke out in the offices of the Cotton Buying Company in Albany Buildings. It quickly spread into Vacuum Oil’s office and some considerable damage was done. However, Wakefield announced that thanks to the quick action of the fire brigade, a duplicate set of records was saved and Vacuum were to continue trading immediately from an office just up the road.

Notwithstanding this optimism, just over six months later, it was suddenly announced in the Liverpool Post that the Head Office of the Vacuum Oil Company had been removed to London and all future correspondence should be addressed to Albany Buildings, Victoria Street, London (This was 47 Victoria Street in Westminster). The Wakefields packed up their bags because Charles Wakefield was now going to be the General Manager of Vacuum Oil for Great Britain and the Colonies based at the London office.

London Beckons

It was a time of great change for Wakefield and he soon adapted to life in the capital. He lived on Pendennis Road, Streatham – in a house he named Campher, an older spelling of a product then made artificially from turpentine and something he doubtless knew well!

By 1896 he was a member of the London Chamber of Commerce and also a Fellow of the Royal Geographic Society. His frequent travels and knowledge of international trade made him an expert in those fields. He met Robert Louis Stevenson in Samoa in the early 1890s and he and his wife were in Japan in the mid-1890s during the first Sino-Japanese war. They also travelled to Russia.

In March 1986 Whittaker’s published his first book, Future Trade in the Far East. In it he shared knowledge of trade routes and in particular information about the Trans-Siberian Railway, then under construction. An interest in steam engines – because of their need for lubrication – had led to a fascination in the world of railways. He was also immensely keen on international relations, something which we will see more of later.

The first of several books written by Wakefield during his lifetime

By 1897 he was connected to the Wesleyan Churches at Streatham and Brixton Hill and he was Senior Society Steward. He took presidency for many meetings including Temperance gatherings and general church meetings. Also by 1897 he was also a steward for the Orphan Working School in Haverstock Hill, North West London, one of many similar roles he would later take. The Methodist Church was a prime mover on adoption and in 1869 a Methodist minister Thomas Bowman Stephenson had founded the first Children’s Home – a renovated stable in Church Street, Waterloo. In 1871 the Wesleyan Methodist Conference approved a second home and by 1908 the project morphed into the National Children’s Home (Today still going as Action for Children). Wakefield became a General Treasurer of the NCH. His love for children, in particular disadvantaged ones was evident. As Harold Murray, the great educationalist and schools inspector remarked;

What did excite me was to see Lord Wakefield, his kindly face all sunshine, sitting on the platform at the Queen’s Hall with a little orphan child on his knee during a performance in connection with the National Children’s Home; and that I saw more than once.

It was in 1898 that what was probably Wakefield’s most momentous lifestyle change came about. Working for Vacuum Oil meant he was an employee, albeit well-paid but an employee nonetheless. He was now almost 40 and highly-experienced in the lubricants realm. He travelled the world chasing orders and had built up a bank of clients, colleagues, and friends. And so, after a row with his Vacuum Oil bosses, Wakefield took eight of his employees with him and established C. C. Wakefield and Company, who traded product known as Wakefield Oils. The lubricants were used for steam engines and heavy machinery and the business was based in the City in three small rooms at 27 Cannon Street. Wakefield was the boss and he was supported by James Browne as Managing Director (and later Secretary), and Walter Ripley Graham, Sarah’s brother. Browne was born in County Donegal in 1865 and Graham in Liverpool in 1854.

The new business did not curtail Wakefield’s desire to make the world a better place. In the early 1900s his interest in children’s homes and orphanages was presumably what inspired him and Sarah to go one step further. In March 1901 a girl christened Lilian Lora, was born to William and Emily Lye. William was an old soldier who now worked as a gardener, travelling to various parts of the country in pursuit of work. Although Lilian was born on the Isle of Wight the couple had married at the Wesleyan Chapel in Southend in 1898 and so the Wakefields probably came to know of them through Wesleyan circles. Two years after Lilian’s birth, Emily gave birth to twins Cecil and Dorothy. Sadly Emily died two days later and neither child survived the month. This clearly had a massive effect on William and his children. Although he would remarry in 1905, for reasons we cannot be sure of, he felt unable to continue looking after Lilian which is how, by 1907, Charles and Sarah Wakefield had adopted her as their daughter. Before the 1926 Adoption Act, there was no official and legal process of adoption and such arrangements were normally private or perhaps arranged through a charity or the church. Lilian’s name was changed to Freda Wakefield and some newspaper reports, mentioning her appearances with her father at various civic events, sometimes referred to her as his niece. This was soon corrected though and Freda became very much part of the family. We shall hear more of her soon.

Shortly before the adoption, the Wakefields had moved to south east Essex. At the 1901 census they were lodging with the Agar family in Prittlewell (Where incidentally, the remains if a Toc H chapel can still be found in the parish church). Wakefield is described as a manager for an Oil Colour Merchant. Also lodging with them is Walter, Sarah’s brother, similarly described. They would later live in a large house The Leas, on the front at Westcliff.

It was not all about liquid oils and lubricants for the business. In 1903 they introduced Carbic Cake which was a solid fuel used in portable flare lights for contractors’ use. They would later claim it to be an improved method of packaging the ingredients for acetylene and exhibited a Carbic acetylene lamp at Olympia.

Civic Life

In 1904, Wakefield took a major move into public service when he joined the City of London Corporation, probably the oldest local authority in the country. He was elected a Common Councillor representing Bread Street ward on the Court of Common Council.

He remained committed to the Freemasons having joined Streatham Lodge in 1898 when the family moved to London, and in 1902 became a member of the Westcliff Lodge. He joined the Guildhall Lodge when it was formed in 1905 (becoming Master in 1915). He was also Patron of the Royal Masonic Institution for Boys, Patron of the Masonic Nursing Home, and a member of several other groups including the Anglo-Brazilian and Anglo-Argentinian Lodges, reflecting his interest in international trade and relationships. And he was listed as a PAGDC (Past Assistant Grand Director Ceremonies) – phew!

As Junior Grand Warden of England

By the early 20th century, Wakefield had become a great collector of art specialising in modern Dutch Masters. His extensive and valuable collection included works by Jozef Israëls, Bernard Blommers, and Johannes Weiland as well as numerous water-colour drawings by Myles Birket Foster, the British illustrator, engraver, and watercolourist.

With art, as with everything, his generosity knew no bounds and from 1911 he helped the Corporation of London build their own gallery, and that which became the Wakefield Collection. Works acquired with his help include Sir George Frampton’s bust of Queen Mary, and Holman Hunt’s The Eve of St Agnes. His srt donations continued throughout his life. He also purchased the seal of Dick Whittington for the Guild Hall.

In November 1906 a ‘large and influential deputation of citizens’ presented the Lord Mayor with a requisition requesting Wakefield be appointed Sheriff the following June. He was so nominated in April 1907 and elected by a show of hands from the liveried companies and much pomp and ceremony at the Guildhall in June. The appointment as Sheriff took effect in September and lasted for a period of one year.

As Sheriff in 1907

Wakefield was described as a citizen and haberdasher at the time, the Haberdasher’s Guild being his mother Guild but he was a member of nine other livery companies at the time, a unique feat. These were the Worshipful Company of Loriners, Spectacle Makers, Gardeners, Gold and Silver Wire Drawers, Cordwainers, Masons, Tinplate Workers, Playing Card Makers, and Turners. He served at various times as Master of the Haberdashers, the Cordwainers, the Gardeners and the Spectacle Makers Companies.

Additionally, he was a member of Billingsgate Market, of Bridge House (The body responsible for the Thames bridges within the City), and of the Sanitary Committee of the Port. At various times he was also President of the Bethlem Royal Hospital, and a governor of St Thomas ’s and Bart’s Hospitals…I could go on. To list every honour or award he got; every position of authority – whether paid or honorary – that he held; or to list every donation he ever made, would fill a book of great size.

By the time Wakefield became Sheriff for 1907, his daughter Freda was taking an active role in proceedings. That year she was Lady in Waiting for the Lady Mayoress Elect, Lady Bell. She was also a Maid of Honour in 1911 and would support her father in his myriad roles.

Freda, far right, as one of Lady Burnett’s Maids of Honour in 1912

Toward the end of his year as Sheriff, in June 1908, Wakefield was elected as an Alderman for the Bread Street Ward and that same month was knighted for his services to the City of London in the King’s Birthday Honours.

Enter Castrol

And if the Civic element of his life was doing well, his already successful business was about to go stratospheric. It was a simple enough idea, if you were as knowledgeable about lubricants and lubrication as Wakefield and his team clearly were. C. C. Wakefield and company decided to improve their popular lubricant with the addition of castor oil. The new brand would be called Castrol to reflect this (Interestingly it appears as Cashol in some early adverts but this might be a case of wrongly interpreting someone’s handwriting as much as anything else). Over the previous decade C. C. Wakefield had moved from focussing on heavy machinery and steam engine lubrication systems to the growing world of motor car and aeroplane engines. At around the same time as it introduced Castrol, the company began to be associated with the sponsorship of motoring events. In particular, in October 1910 the company and its new Castrol branded oil appear in adverts for Claude Grahame White and the Gordon Bennett trophy. White was one of England’s aviation pioneers who earlier in the year made the first ever night-flight during the London to Manchester Air race, itself the first long-distance air-race in the country. White then won the prestigious American Gordon Bennett trophy in New York flying a Bleriot XI and using Castrol oil.

Wakefield had been interested in aviation since its start. Flying as a sport got off the ground (Pun intended) in England in 1909 after the first national aviation meeting was held at Doncaster racecourse in October. Wakefield Motor Oil, not then rebranded as Castrol, performed admirably in several of the aircraft that were breaking records at that meet. Soon afterwards Wakefield presided over a meeting at Drapers’ Hall to publicise the sport. At that meeting he made a speech which the media in part was compared to Jules Verne or H G Wells in that the predictions were so futuristic. Talking about the success the Germans were having with their Zeppelin programme, Wakefield predicted heavier-than-air craft that might reach speeds exceeding 120mph. He predicted transcontinental transport carrying both passengers and goods – this at a time when aeroplanes were lucky to get one man into the air let alone two. He even painted a picture of aerodromes all over the country lit up at night with neon signs proclaiming their names. He mentioned mail delivered by air and air-taxis. It was, without doubt a prophesy of Nostradamic proportions.

Coming back down to earth and to his business, in 1910 a spin-off company, Carbic Limited, was floated to acquire the rights to produce Carbic Cake (along with the brand names Carbric, Brillia, Setlyne, and others). The directors were Wakefield and Browne of C. C. Wakefield along with W. M. Letts and Walter F. Reid.

The main business itself was doing splendidly and a decision was made to move to a new building on Cheapside, just around the corner form the Cannon Street offices they had occupied for some dozen years. This led to a story that would have stirred Tubby’s interest; in 1912 whilst workmen were preparing the site at 30-32 Cheapside (which would become Wakefield House), they unearthed a buried wooden box under the cellar. The box contained some 400 pieces of Elizabethan and Jacobean jewellery, including rings, brooches, and chains, with bright coloured gemstones and enamelled gold settings, together with toadstones, cameos, scent bottles, fan holders, crystal tankards and a salt cellar. This collection became known as the Cheapside Hoard and is mostly held by the Museum of London. The company moved into their new premises in October 1913.

Wakefield House, Cheapside

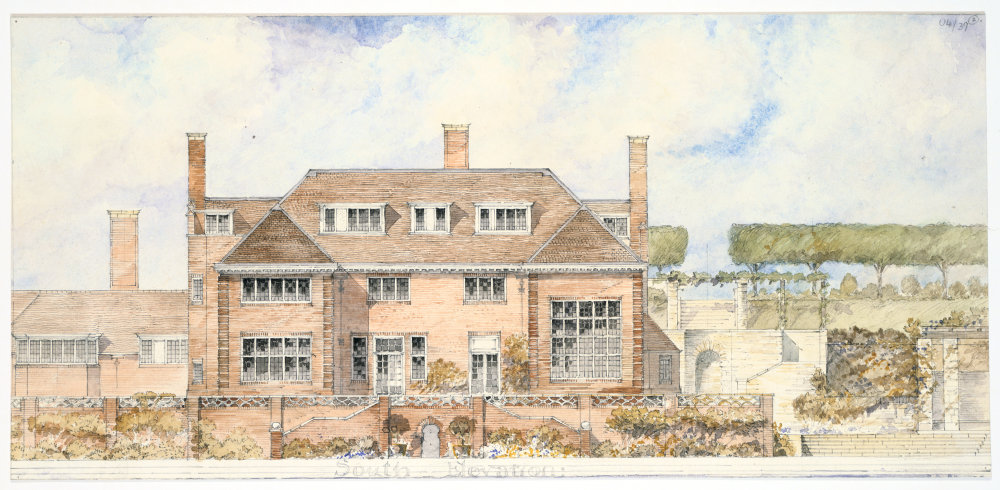

Discovering Hythe

On the move too were the Wakefield family themselves. Having broken down whilst driving down Black House Hill, on the way in to Hythe in Kent, and whilst waiting for assistance, Wakefield remarked what a beautiful place it would be to live. Soon after he bought White Cottage on the hill and some adjacent land. In 1913 they were having a new house, to be called the Links, built on the land. An area with commanding views over the channel and Romney Marshes, it was, as the house name suggests, alongside Hythe golf course, Wakefield being a keen golfer (He would later be President of the Kent Professional Golfers’ Union). Inside the new house went a staircase, wooden panelling, mouldings, pediments, and some other items rescued by Wakefield from an old mansion in Botolph Lane in the City of London condemned in 1906. Sometimes referred to as Wren’s house in the city, the old City dwelling belonged to the John Cass Institute. Wakefield bought the items to prevent them going to America.

Wakefield came to love Hythe almost as much as the City of London. He frequently extolled the health virtues of the town, even calling it Dr Hythe although how healthy the house truly was is another matter. Water pressure at the top of Black House Hill was virtually non-existent and the handful of residents were frequently trying to get the council to install a better supply.

Design for The Links, Hythe: south elevation. Courtesy RIBA Collection

The Wakefields continued living in White Cottage even though the new house was finished; Sarah found it too large for entertaining. Thus when war broke out they immediately offered it to the military. In fact, by Christmas 1914 Wakefield had over two hundred soldiers of Kitchener’s army billeted there and he laid on Christmas dinner for all of them. He later said that for a time he lived amongst “250 of Kitchener’s army and had never seen such chivalry amongst men.”

Recruiting in the Guildhall, London by Fred Roe (City of London Corporation) http://www.artuk.org

The War Years

This brings us nicely on to Wakefield’s military connections. Despite his strong religious conviction, Wakefield was not an outright pacifist and he saw value in instilling some discipline and military skills in young people. Hence, in 1913 he presented the Guildhall Cricket and Athletic Club with a rifle range. By this time he was already a member of the City of London Territorial Force Association. In the autumn of 1915, he was elected Lord Mayor of London, a considerable honour but most well-deserved and at the time of his election, he became an Honorary Colonel with the 26th (Service) Battalion the Royal Fusiliers. A battalion raised early in 1915 – from bank clerks and accountants – by his predecessor as Mayor, Sir Charles Johnston, along with Major William Pitt. It was, inevitable, known as the Bankers’ Battalion.

Wakefield in uniform

Wakefield was of course facing the challenge of being a Mayor during wartime but he was well suited to the task and highly-motivated, particularly regarding recruitment. On 10th January 1916 he opened up Mansion House as a recruiting office. He took an energetic part in the recruitment drives for the forces during the First World War.

Inspection Of The London, Brighton And South Coast Railway Hospital Train

In May 1916 the 26th Battalion went to France and took part in various battles of the Somme before moving on to Flanders. Wakefield paid visits to the Western Front in 1916, and also to the Grand Fleet in Scapa Flow. He offered a £500 reward to the first person to bring a Zeppelin down on British soil.

Perhaps most interestingly to this group, he did much to raise funds for the YMCA huts that provided “home club life” for troops both at home and abroad. Whilst not quite providing that authentic home from home that Talbot House achieved, the YMCA huts did a most important job. Barclay Baron was one of those closely involved with their running.

Inspecting Trinidadian troops

The Wakefields lived in Mansion House for his year of office but went to Hythe whenever it was possible. Religion remained important to Wakefield but his interaction was not limited to the Wesleyan church. Whilst Lord Mayor he presented a proposal to hold a conference at the Manor House to reconcile denominations and create a united British church. It met with a lack of interest and enthusiasm among church leaders.

A Church Warden at St Mildred’s in 1916, he made history from the outset of his term as he became the first London Mayor to demand that his inauguration parade stopped outside St Paul’s Cathedral so he could go in and pray.

Leaving St Paul’s on the day of his inauguration

His religious outlook, his remarkable work in recruitment and support of the troops, and his philanthropic nature in general helped make him a very popular mayor. So successful was his tenure that many of his colleagues wanted his mayoralty extended by a year as he was doing such a fine job in lifting the morale of the city. Wakefield himself rejected this on the grounds that – though honoured – he did not wish to stop any of his fellow Aldermen from having their year in the spotlight.

Entertaining wounded soldiers at Hampton Court 1916

This public success during the war years was tempered – as was the case for most people – by personal tragedy. In Wakefield’s case it would most pertinently be the loss of two cousins – sons of his Missionary uncle Thomas. Leonard John Wakefield of the London Regiment (Post Office Rifles) died in June 1917 and Leonard’s brother Thomas Butler Wakefield of the West Yorkshire regiment died a few weeks later in September, both in France.

During and after his tenure as Mayor, honours continued to be bestowed upon Wakefield. In May 1915 he was appointed a Knight of Grace of the Order of St John and on the 16th February 1917 created a Baronet of Saltwood in Kent. Two years after that Wakefield was Created Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE).

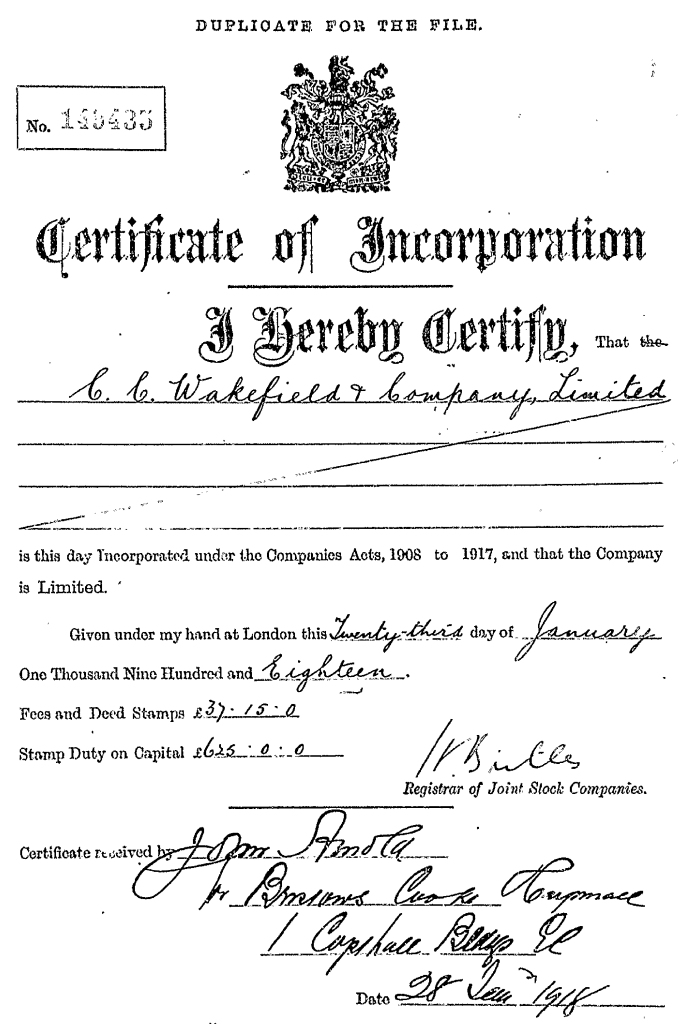

With his 20 HP Crossley

In the middle of getting these honours, on the 23rd January 1918, C. C. Wakefield and Company, was incorporated with the shareholders being Wakefield, James Browne, and Walter Graham, the former directors of the earlier company. Despite the fact it was increasingly known for its main Castrol product, the company did not change its name to Castrol until 1960, long after Wakefield’s death.

Post War

After the war, and with his mayoralty over, Wakefield continued as before. One interesting occurrence came when in July 1918 it was announced that Wakefield had bought the original Hell Fire Corner Board from near Ypres and installed it in his garden. I have no idea if it survived, and it seems there was actually more than one of these boards.

Continuing to live in White Cottage rather than the now empty Links next door, Wakefield was taking a great interest in the affairs of Hythe. In March 1920 he became a Justice of the Peace and a year later became a member of the newly formed Hythe Chamber of Commerce. As always, he was keen to help sports people out and he financially supported Hythe Football Team even becoming their President. Wakefield attended home matches whenever he could and always bought the ball after the cup final. In January 1922 he opened the Hythe British Legion club and donated £200 towards it. They had approached him to borrow the money but he said he never lent money, donating it instead. He also supported the Hythe Association of ex-Servicemen.

With Hythe football team 1922

Several Boys and Cadet camps were held in a field near his house and he usually laid on refreshments from them. These included the Duke of York’s Camps which Toc H was involved with so it’s quite likely Wakefield had some dealings with the fledgeling Movement, perhaps the likes of Henry Willink who attended many Duke of York Camps, at this time. Whilst the Links had proved too large for hosting intimate dinner parties, it’s huge terraces and large Italian gardens proved useful when the Wakefields entertained 400 boys from these camps at their house! And in 1926 he nailed his political colours to the post when he became President of the Hythe Conservative and Unionist Association.

In August 1921 Lady Wakefield was recognised for her war work receiving a Gold Medal from British Red Cross. She was very involved in charitable work particularly that regarding the welfare of soldiers but also organisations that supported women. As Lady Mayoress during the war, she went to great efforts to reduce the civic functions taking place at Mansion House, and kept her entourage of Ladies in Waiting and Maids of Honour for only the grandest occasions, looking after her own affairs for much of the time.

Her husband’s support of aviation continued perhaps most notably with the provision from 1920 of several annual scholarships for the RAF. These scholarships were endowed to assist in defraying the expenses of the Royal Air Force College, for Flight Cadets whose parents or guardians were in reduced circumstances, and to certain Aircraft Apprentices who were selected for cadetships. Five scholarships, each of the value of £75, were awarded (three to Flight Cadets and two to Aircraft Apprentices).

We have already spoken about Wakefield’s interest in trade and foreign relations and he was very involved with the Sulgrave Institution, which promoted Anglo-American co-operation. It was based around the village and manor of the Northampton village of Sulgrave whence George Washington’s ancestors came from.

In September 1922 the family travelled to America with Wakefield heading a party from the Institute. They were to present the American people with a bust of William Pitt, two of Viscount Bryce, and a statue of Edmund Burke. They also presented a wooden pew from Sulgrave church to their hosts. Freda unveiled the bust of Bryce, a former Ambassador to the US, in New York.

British Delegation from the Sulgrave Institution (L-R) Rev. G.C.F. Bratenhal, Wakefield, Freda Wakefield, John Weeks, Alton B. Parker & Lady Geddes

Wakefield was also chairman of the Czech Society of Great Britain being awarded the Order of the White Lion, the highest Czech award, in 1923. He wrote a privately published pamphlet about the trip. Wakefield would also write America to-day and to-morrow: a tribute of friendship in 1924, and On Leaving School: and the Choice of a Career in 1927.

Wakefield’s interest in aviation continued and reached new heights in 1924 when a De Havilland 50 he owned won the prestigious King’s Cup for the Round Britain Flight. It was piloted by Alan Cobham, a test pilot for de Havilland and one of aviation’s true pioneers. On being awarded the cup, Wakefield stated that light aircraft competitions marked in epoch in aviation and in ten years’ time young people would take to the light aeroplane as a sport and hobby as they did to the motorcycle and two-seater motor car!

Two years later Wakefield would finance Cobham’s return flight to Australia and in 1929 launched Cobham’s ‘Youth of Britain’ aeroplane by severing the rope that tied it to the ground, with an axe.

Perhaps most famously, in 1930, Wakefield would help fund Amy Johnson’s flight to Australia, the first solo flight from Britain to Australia by a woman.

In 1931 Bert Hinkler would praise Wakefield’s sponsorship and support when he made the first crossing of the Atlantic in a light ‘Puss’ Moth as well as shattering many other records and in 1935 a Castrol endorsement contract and the generous patronage of Wakefield provided the funds for Jean Batten to purchase the Percival Gull Six G-ADPR monoplane in which she made a solo trip from England to New Zealand.

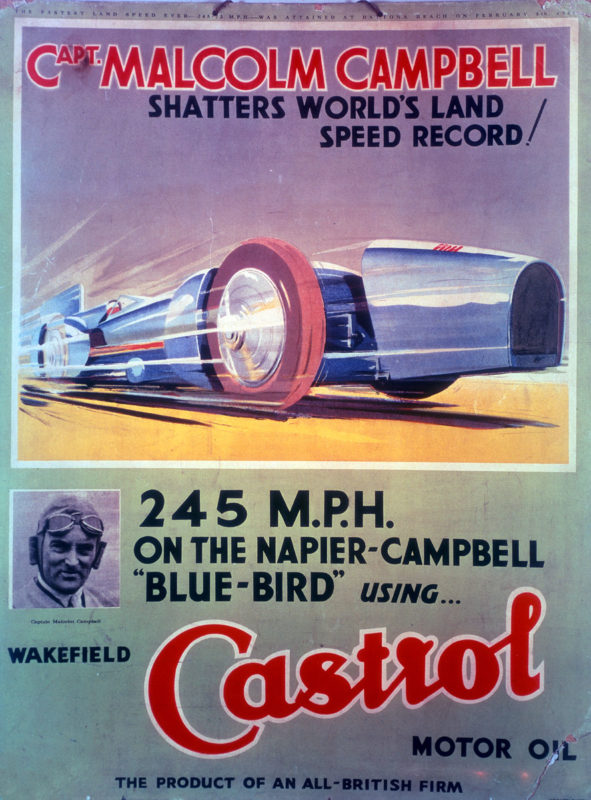

Motor sport was also close to his heart. He supported Sir Henry Segrave’s speed trials in the USA; was the donor of the Wakefield Gold Trophy for the world land speed record, first awarded to Colin Campbell in 1928. Wakefield laid on a celebratory lunch for Sir Malcom Campbell after he drove the Napier-Campbell Blue Bird at a shade under 207mph in Daytona. Two years later, Segrave would reclaim the land speed record – lost briefly to the US for the UK travelling at over 230mph.

Segrave was also a beneficiary of Wakefield’s support on the water. During the twenties and thirties Segrave and Kaye Don used a series of speedboats named Miss England to contest world water speed records. All were built for Wakefield, the first being built in Hythe. Miss England II was built in 1930 after Wakefield had obtained a pair of new Rolls-Royce type R V-12 air-racing engines. Miss England III was the last of the series. She was delivered to Wakefield on 9 May 1932 and two months later Don set a new world water speed record of almost 120mph on Loch Lomond.

1926 would be a particularly interesting year for Wakefield, especially in the terms of this blog. In September his daughter Freda married Ivor Ormonde Corry Ware at St Nicholas Cole Abbey in the City. She used her birth name of Lillian Lorah Lye but she recorded her birth father as deceased even though he didn’t die until 1953.

However, a few weeks before that, on 1st July 1926, Wakefield met Tubby for the first time. It seems inconceivable that he was unaware of Toc H given his philanthropic nature but there is little to suggest he had had any substantial contact with them prior to this date. The meeting came about when Tubby, as Vicar of All Hallows, was approached in June by the men of the Corn Exchange in Mark Lane and asked to arrange some prayer meeting to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the first day of the Battle of the Somme on 1st July. He agreed to hold a fairly low-key service at All Hallows.

Wakefield had been Lord Mayor of London when the Somme took place so Tubby sent him a telegram to Hythe on 30th June to invite him to join them for prayers were he coming up to the city then following day. Following early morning services at 6am and 8am, a special commemorative service was held at 1.05pm. The current Lord Mayor, Sir William Pryke, attended accompanied by his Sheriffs. Six Toc H men acted as Stewards.

Tubby made a stirring tribute to the fallen including the following:

This ancient City has many faults but forgetting her debts is not one of them. The only way of paying this great debt is by loyalty to God and greater loyalty between man and man.

Wakefield had attended and afterwards met Tubby. Also joining them was Paul Slessor thus starting a lifelong friendship but it was Wakefield and Tubby who immediately hit it off

What occurred that day, in All Hallows, was the coming together of two men. Neither was born in London but both loved that City and its rich history. One was a former Mayor, the other incumbent in one of the oldest churches in London. Both men had played vital supporting roles in the war and were keen to both remember the fallen and look after those who survived.

Tubby had dreams and plans to turn Tower Hill into a garden space for City workers and nearby residents alike. He shared those dreams with Wakefield that day and the businessman pledged his support.

Then in 1929, Wakefield was at the heart of something that holds him dear in the heart of all who loved and who love Toc H. It began in September 1929 when Tubby wrote a letter to the Times. In it he spoke of viewing the mine crater at St Eloi whilst on a Toc H pilgrimage when the party sat for an hour by the crater side and “watched a beautiful sunset repeated in it.” In the letter he said that men of two races lay beneath it. He also said that the rest of the craters were now filled in and growing kitchen produce (Not quite true as it happened), and suggested that St Eloi be purchased and preserved as a tranquil pool of peace.

One man who read this letter was Wakefield. He immediately offered to buy the crater for Toc H. After discussions with the Imperial War Graves Commission, it was decided that Lone Tree Crater would be a better option and Paul Slessor – with his multi-lingual abilities and business experience – was dispatched to make negotiations. The crater was purchased on behalf of Toc H and renamed the Pool of Peace. It remains so to this day.

Wakefield was pleased with how things went and asked if he could be of further service. It just so happened that Talbot House itself was potentially for sale and once more Slessor was sent to Flanders to negotiate. At the 1929 Birthday Festival in December, the Prince of Wales was able to announce that Talbot House had been bought for the Movement (Although it would actually be owned by an Anglo-Flemish organisation to satisfy Belgian property law). Wakefield stumped up the purchase price along with a £10,000 endowment towards its running. Although in limited use in 1930, it was not officially opened until Easter 1931 when Wakefield himself turned the key to open the door and lead the party inside.

The opening of Talbot House Easter 1931

Whilst all this was going on, Wakefield had a lucky escape in August 1927 when he was on the London to Deal train returning home to Hythe. It derailed near Tubs Hill station, Sevenoaks killing over a dozen passengers. Wakefield injured his knee in the crash. Though not serious – he continued to Hythe by car – it was an injury that remained with him the rest of his life.

More Honours and Titles

More positively honours continued to be bestowed on Wakefield. On the 21st January 1930, he was raised to the Peerage as Baron Wakefield of Hythe in Kent and created a Freeman of the Borough of Hythe on 30 May 1930. On the 28th June 1934 he would be promoted in the Peerage to become Viscount Wakefield of Hythe. He was appointed GCVO (A Knight of the Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order) on the 23rd June 1936, one of only six such appointees during Edward VIII’s short reign.

Back in the City in 1935 Wakefield became the first member of the Corporation to be made an Honorary Freeman, invited by the Court of Common Council to take the Freedom rather than applying for it. It is the highest honour that can be bestowed by the City and he shared it with a few notables such as Churchill, Pitt the younger, Gladstone, Montgomery, and Florence Nightingale.

Tubby once said “Lord Wakefield has so many titles and so many accomplishments that I don’t quite know whether to salute him as Colonel of the Fusiliers or as an author, nor do I know when I shall come before him as a beak ”

And whilst not as formal as the official honours given him, I have little doubt Wakefield was charmed by Tubby’s gift in return for his generosity to Toc H. Tubby presented him with a signet ring dropped in the offertory box by an unknown pilgrim during the summer of 1930, a most special treasure.

The reopening of Talbot House was the high-point in a period where Wakefield was very active for Toc H. In 1930 he funded the Skittle Alley in the basement of 42 Trinity Square (The other Talbot House which I have written about extensively here . Wakefield bowled the first ball and he and Neville Talbot were beaten by Sir Henry Segrave – the land speed record driver – and Lord Middleton – a Vice President of Toc H – after which members of the Royal Automobile Club bowls team gave a demonstration.

Opening the skittle alley at Talbot House (42 Trinity Square)

Wakefield also bought the house next door (41 Trinity Square aka Wakefield House) which served many purposes including use by Toc H. It was intended to be demolished to extend the park but like 42, 41 remains standing to this day the last Georgian buildings on that side of Trinity Square. In 1937 his bust would be installed on the front wall of Wakefield House.

One of the terraced Georgian houses in the Crescent, backing on to Trinity Square, was also taken by Toc H and named Lady Wakefield House.

In 1931 he was elected as a President of Toc H and also served a three-year term on Council.

But it was in 1933 that Wakefield helped Tubby’s other project, the one that the two had talked about that their first meeting in 1926, get off the ground when on 28th April 1933 the Tower Hill Improvement Company was incorporated and ready to commence business from the 27th June 1933. In October Tubby and Dr Bertram Ralph Leftwich published The Pageant of Tower Hill, which included the outline of a scheme to improve the Hill – the Commendation was written by Wakefield. Then in December 1933 the inaugural meeting of the Tower Hill Improvement Fund was held. Lord Wakefield was elected President and launched an appeal at the Guildhall in January 1934 in his position as Alderman of the City. The scheme to turn the Tower Hill area into a place of entertainment and relaxation for City residents and workers was underway.

The first significant outcome of the scheme was the opening of the Children’s Beach in July 1934. Wakefield performed the opening ceremony cutting a ribbon at the top of the gangplank leading down to the beach. This same year Wakefield sponsored volunteers for the Toc H/BELRA leprosy scheme, one of the latest of Tubby’s passions.

Until now, Wakefield’s financial contributions had mostly been made directly but in 1937 the Wakefield Trust was established. Many of the properties in Trinity Square and the Crescent, mentioned above, as well as dozens of others, were purchased by, or transferred to, the Trust.

Part of the process required the destruction of old warehouses on Tower Hill and on the 18th March 1937, Wakefield presided over a high-profile demolition of such buildings. Wakefield rang a bell after which a series of explosions ran along the building. At each explosion – and the last failed – a piece of brickwork toppled backwards. Not though because of the explosions, they were only magnesium flares for show, but rather because a team of navvies from demolition company Goodman Price were hidden behind the warehouse and tugged at ropes slung around the brick until they fell. There is some lovely Pathe footage of this event here.

Ringing a bell to begin the demolition of warehouses on Tower Hill

We destroy only to create upon this site a new garden for London’s citizens, young and old

The land where the warehouses stood became a small park known as Wakefield Gardens. It remains so to this day and is that open space just outside Tower Hill underground station.

Further gifts to Toc H included the funding for Harington House in Gibraltar in 1938 and the following year he gifted a site – I think Tower House a few doors south of 42 Trinity Square – and £2000 for a new Toc H headquarters to be built. The outbreak of war meant this never happened and Toc H would have to wait another 20 years before finally getting their HQ on Tower Hill.

As well as Toc H and his sporting interests, Wakefield maintained keen support of the NCH. In 1931 it was announced in the press that Lord Wakefield had donated £8,000 to their Home and Orphanage at Alverstoke. This enabled them to add Uxbridge House to the complex there. In accordance with his wishes the name was to be changed to Lady Wakefield House. It became the primary school for the Alverstoke home.

The Final years

The business continued to flourish and in 1936 Wakefield was once again making headlines. On this occasion he decided to scrap the then normal scheme of employees making payments to their pension and decided to pay their contributions himself. Not only that but he refunded them everything they had previously paid in. It was a costly exercise but typical of his great generosity.

With the outbreak of the Second World War Wakefield’s company headquarters was evacuated to Knotty Green in Buckinghamshire (A fortunate move since the Cheapside office was bombed shortly afterwards). Wakefield himself rented Ashwell Lodge nearby in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, a quiet doctor’s house.

His support of Toc H continued and he paid for Tubby and his cousin and Aide De Camp Peter Le Mesurier to tour India in 1939. They ended up on Orkney where Tubby and Toc H undertook important war work (The Toc H Orkney story is planned for next year). Inevitably Wakefield paid for much of this work.

Tubby made sure to visit his friend in Beaconsfield when he got leave from Orkney in the summer of 1940. Pettifer joined them there. The Chief, as Tubby called Wakefield, assembled his staff on the lawn and made Tubby talk to them about what was happening on Orkney and then Wakefield spent some time chatting to Pettifer; he loved nothing more than a chinwag with a veteran. He also did something he had never before done and passed two crisp £5 notes to Pettifer. This was a lot of money back then and Pettifer, a working class, virtually retired Londoner, was most appreciative. It would be the last time Tubby and Pettifer saw Wakefield.

Whether for his oil business, civic duties, Toc H or other philanthropic causes, Lord Wakefield never slowed down. In December 1940, the day after his 81st birthday, he became unwell and sadly died on the 15th January 1941. Tubby heard the news on the radio whilst at Inverness on his way south from Orkney. It was a dreadful time for him. All Hallows had just been destroyed in the Blitz, his old-friend Robert Baden-Powell had died a week earlier, and the day before Wakefield, Tubby’s long-term colleague in Toc H William J. Musters died suddenly and unexpectedly. Now this! Tubby had intended to visit Wakefield at Beaconsfield once he was back down south and was stunned to hear of his death. It also, by tragic coincidence, occurred just a week after Amy Johnson – one who had benefited from Wakefield’s sponsorship – crashed in the Thames estuary and was lost, her body never recovered.

Charles Cheers Wakefield, was buried at Spring Lane Cemetery, Hythe on Saturday the 18th January. The cemetery lay on the far side of the golf course by his home. Tubby officiated, assisted by the Rev. Cyril Norris. The Archbishop of Canterbury gave an address. At Wakefield’s request there were no flowers.

It snowed during the service and Tubby said that,

“each flake a ‘Thank You’ from a London child”

The Memorial Service was in the Crypt Chapel of St. Paul’s Cathedral – the High Altar having received bomb damage – on Wednesday 22nd.

Caricature by Sirra

Legacy

A new board was founded to run his business with the motorcar racing driver Captain George Eyston as one of the directors (and competitions manager). In 1960 the company finally changed its name to Castrol, its most famous brand and it continues to exist to this day.

He left his wife Sarah financially secure – she died in February 1950 – and he left Freda, her husband Ivor and her four children a living each for their futures.

Hythe’s greatest benefactor, he is remembered with many memorials in the town. The Freemasons honoured him by creating Wakefield of Hythe Lodge in his memory in 1945. Civically one particular tradition remains: each year at the town’s Mayor Making, a few moments of silence are observed in the Town Hall as the new Mayor hangs a wreath by the portrait of Charles, 1st Viscount Wakefield of Hythe.

From Toc H’s perspective the link between Hythe and Poperinge was cemented by a twinning arrangement and the Poperinge Saint Cecilia Band often visits Hythe to play at festivals and festivities.

In an age where it seems the majority of our wealthy business man care only about increasing their wealth, Wakefield puts them to shame. He changed the lives of hundreds of thousands of people for the better. He made the world a better place. And for those of us who know Toc H, we will be forever grateful that thanks to Charles Wakefield, Talbot House remains a haven of peace and reconciliation to this day.

Portrait by John Lavery

Acknowledgments

An article like this finds information from a vast array of resources. In particular I am grateful for the following books, journals, and websites.

A Proud Citizen by Harold Begbie (Hodder & Stoughton) from which many of the uncredited image sin this article were taken

A Fool for Thy Feast – Linda Parker (Helion)

Clayton of Toc H – Tresham Lever (John Murray)

Tubby Clayton – A Personal Saga – Melville Harcourt (Hodder and Stoughton)

Tubby Talking LP (Toc H)

The Toc H Journal (Now available online at archive.org/details/toc-h-literature)

Grace’s Guide To British Industrial History (gracesguide.co.uk)

The history of Hythe in Kent (hythehistoryblog.wordpress.com)

A Dictionary of Methodism (dmbi.online)

Ancestry (ancestry.co.uk)

Find My Past (findmypast.co.uk)

The Internet Archive (archive.com)

Just splendid. Thank you for this wonderful research.

LikeLike

Thank you Luc

LikeLike

I have a 1927 copy of AUTONIOGRAPHY OF A FISHERMAN by Canadian author Frank Parker Day. The inscription just inside the front cover is identified as being from “Sir Charles C. Wakefield/ex-Lord Mayor of London.”

The 3-line inscription reads:

So may we live, love work, love play

That when we grow to weary to feel joy

Leave life with laughter to some other boy.

Any ideas on the precise origin of this bit of verse??

LikeLike

That’s a lovely thing to have. I’m afraid I can’t help with the verse though. let us know if you get any joy

LikeLike